Labour in Vain

Wander through central Footscray with us while we chat about settler nativism, anti-Chinese campaigns, arts and gentrification, and the grotesque fantasy of a white Australia.

Map

Use the icon at the top left to toggle which tracks are shown, and “star” the map to save it to your Google Maps.

Transcript

ANA Building

Jinghua Qian: So this is where it all started! 42 Albert Street. It used to be the Dancing Dog café, I’d come here for coffees pretty often.

Anyway, this is the place that got me wondering about all the hidden histories here in Footscray.

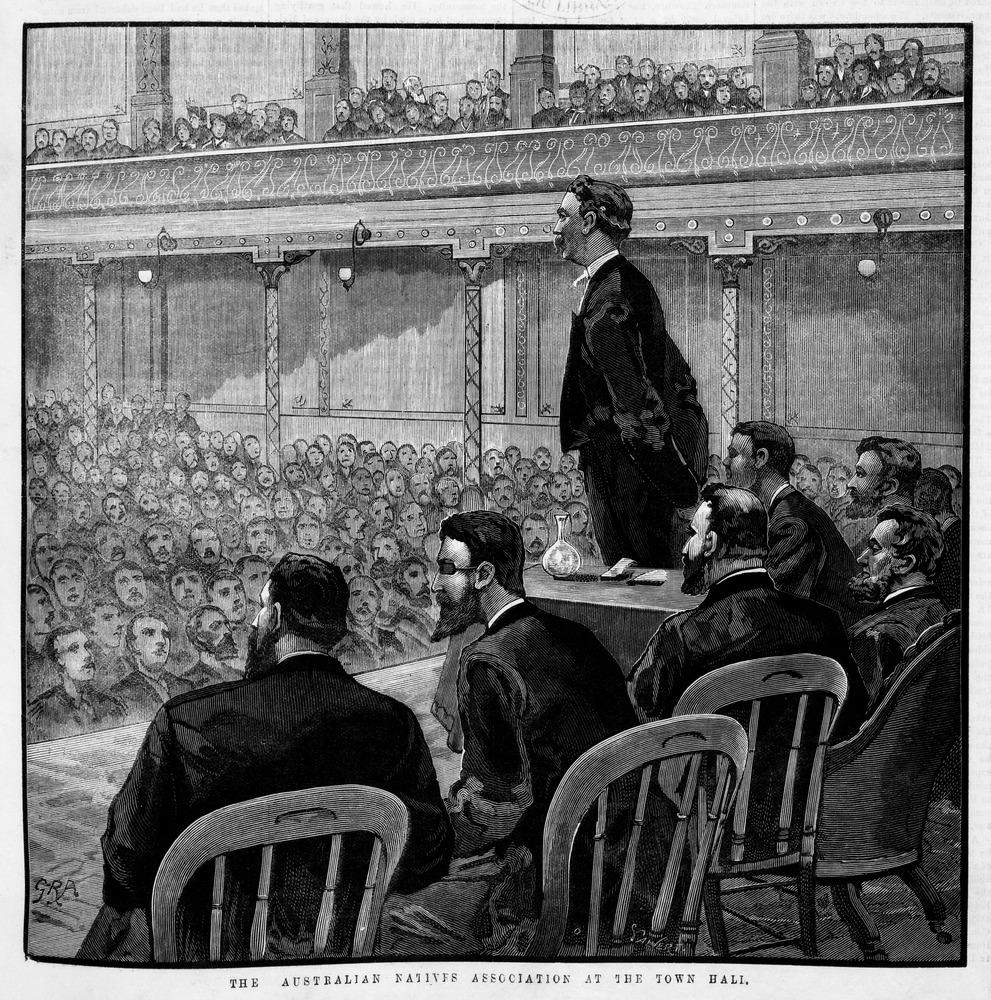

Liz Crash: We both noticed the sign on the top of the building, which says Australian Natives Association Friendly Society. And we both assumed it was an Aboriginal organisation. But it turned out to be a society for white men who were born in Australia. Alfred Deakin was a member, Edmund Barton, a lot of the Federation era politicians. They campaigned for federation and immigration restrictions and protectionism.

Jinghua: It was founded in 1871. Back then, most of the government was made up of people who were born in Britain. So white people who were born in Australia were just starting to develop their own identity around that, in contrast to the British-born, and they called themselves “natives”.

And they would hold “corroborees” celebrating January 26 and one of their emblems had boomerangs on it. So this kind of settler nativist cultural appropriation thing, where white people want pieces of Aboriginal culture but without Aboriginal people, where they sort of position themselves as the inheritors of indigeneity, that was happening a lot earlier than I would’ve expected.

And then on the other hand, the point at which white Australians became Australians, and started to talk about themselves as Australians, that was a lot later than I would’ve expected. I mean this was well after the peak of Chinese gold rush immigration to Victoria. The colony passed the Chinese Immigration Act limiting Chinese arrivals in 1855. It wasn’t until the 1890s that the majority of non-Indigenous people in Australia were Australian-born whites.

So I found that really interesting when I was writing about the ANA back in 2015 because it demolishes the chronology of like, “we grew here, you flew here”, you know? It blows apart the idea that immigration restrictions were about maintaining white Australia — it was about creating it. Colonisation and xenophobia are simultaneous and ongoing, and white Australia is the fragile, spectral thing on the horizon. It’s the apocalyptic future, not a historical moment that can be restored.

Liz: I mean, I did assume it must be some kind of Aboriginal association. But I also thought — well, hang on, it’s really old. Did Aboriginal people really have the kind of resources to get a permanent office in a nice building with a mural and everything, in Footscray, in the 19th/early 20th century? So when I learned it was actually an organisation for white Australian-born people, I was like ah, the world makes sense again. It’s not fair, it’s depressing, but this fits into a narrative I recognise.

But it turns out I was actually still wrong. During the peak of the ANA’s power and influence, Footscray was a major centre of Aboriginal life and culture and political organising.

William Cooper, a local Aboriginal organiser, heard an ANA speaker in 1937 and apparently he was furious they’d appropriated the term “native” for themselves, being colonisers. I knew a bit about William Cooper but I didn’t learn he’d had that critique of the ANA until a couple of months ago actually, and it surprised me. It surprised me because people tend to assume that appropriation is a trivial modern issue that we only care about now that the real problems have been fixed.

Jinghua: But it’s always been both. The racism of a century ago was a lot more subtle and sophisticated than people seem to remember — for instance the Immigration Restriction Act, the cornerstone of the white Australia policy, didn’t make any explicit reference to race. It never actually uses the word “white”. It’s a lot like the dog whistle politics now. So this thing where white people claim that being called white is a slur, or that calling someone a racist is as bad as being racist, or that only the most extreme and literal hate speech can be considered racism, none of that is new. Controlling the discourse of race has always been crucial to enabling racial violence.

Liz: It goes back to what you were saying in the first tour — you can’t count on the future to be better than the past unless you make it that way. I know that but it still surprises me.

I guess that’s kind of what this project is about. Taking things that feel like they have always been the way they are or worse and saying: well, is that actually true? Or is that something that has been different before, and can be different again?

Jinghua: For sure. People usually talk about the white Australia policy as an anti-immigration policy designed to keep people out, but it was equally about destroying the Chinese community that was already here.

Chinese market gardens

Liz: And one place there was a Chinese community was right here, so directly opposite the ANA building, where the train line is now on the other side of Raleigh St, was a Chinese market garden, an urban vegetable farm. There were actually plenty of Chinese market gardens in the Western suburbs, and plenty of Chinese people full stop.

One of the ways the ANA tried to make a hostile environment for Chinese workers was by encouraging consumer boycotts of Chinese goods.

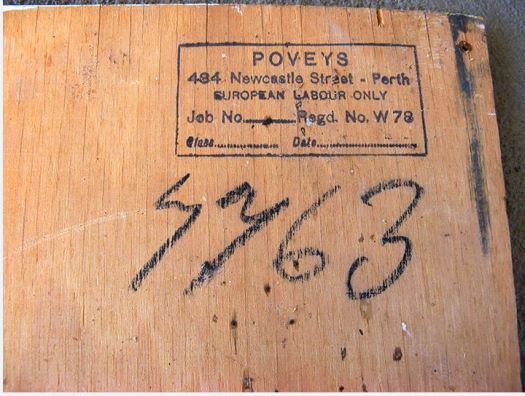

Jinghua: Yeah, they also lobbied for furniture stamping, that’s why you see the “Chinese labour” and “European labour only” stamps on old furniture. It’s like the 1930s version of buying Australian made linen sack dresses, you’d get your white labour chairs and sugar. But there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism! And no ethical consumption under colonisation.

Liz: And in any case, they had a bit of a problem getting these boycotts going because it was women who did most of the shopping. And the white women of Footscray weren’t initially on board. Which is not to say they weren’t racist, but they weren’t racist enough to overlook a bargain.

The anti-Chinese campaigners spent a long time trying to change this, initially not very successfully. The local papers in the 1880s and 1890s are always whingeing that “women above all are the most inveterate of freetraders”. The same papers pointed to the fact that women didn’t participate much in the anti-Chinese consumer boycott as evidence that they shouldn’t have the vote — they were clearly incapable of thinking about things politically or collectively.

This is something you’ve done quite a lot of research on, Jinghua.

Jinghua: Yeah when I was initially researching this stuff for an essay a few years ago, the first thing that really struck me was that these were labour activists. But it wasn’t a contradiction for them to attack Chinese workers in the name of equality because for them, Chinese people were inherently unequal. Like the Prime Minister Edmund Barton said, “The doctrine of the equality of man was never intended to apply to the equality of the Englishman and the Chinaman.”

Liz: Ah, all part of building a democratic nation.

Jinghua: That was the dream, only a white nation could be a democratic nation.

And while we’re talking about the ANA and settler nativism, I can’t help but think about how migrants fit into that, particularly how as non-Indigenous people of colour, we can end up validating this sort of diversity narrative that disappears Indigenous sovereignty. I remember one time Midsumma Festival approached me and asked if I wanted to be in an Australia Day thing because they wanted it to be more “inclusive” and I was just like, oh no. No, that’s not right.

Bunjil mural & African flags

If we go up towards Irving now, you’ll see the big colourful Bunjil mural.

It’s not by an Aboriginal artist, actually, it’s by Heesco who’s a Mongolian Australian artist. He’s done a lot of work around Footscray including the Franco Cozzo mural and the mural at the back of ASRC which has a portrait of Malcolm Fraser and then words like “hope” and “freedom” in different languages.

And then if we turn into Nicholson St you’ll see flags for a lot of African countries. A few years ago I talked to Ihab, a Sudanese Australian artist, about us both feeling like hmm, is this something that contributes to erasing Aboriginal presence here, or absorbs Aboriginal people into this flat multiculturalism. Like, Asians and Africans are so visible in Footscray while a lot of the visual markers of Aboriginal community are sort of memorialising. And you often hear people talk about Footscray as an African or Asian suburb, forgetting whose land it is. So that’s a kind of migrant nativism, I think: it’s another layer of erasure.

Footscray Halal Meats and Club X

Anyway now we’re on my street, Nicholson St. Liz, you have a funny story about the butcher here.

Liz: Right, so this butcher, Footscray Halal Meats, is where I always go to buy meat for my cat. She’s very fussy, she has a delicate stomach. It’s changed ownership a few times but it’s been around since at least the late 80s, when my parents moved here, just before I was born. And my parents also used to go here a lot sometimes with me and my siblings.

My dad is retired now, but he’s a plumber by trade. He’s worked on a lot of houses and businesses in the area. One business that he did the plumbing for in the late 80s was right next door to here, the Club X. Club X is a sex store that also has porn screenings and sometimes live peepshows.

So, my dad was going to Club X every day, via the back entrance, thinking obviously that he was getting away with something, but the butcher saw! He saw this man spending all day skulking in the sex store, leaving his partner at home to sit in a dark room and do god-knows-what for hours.

My poor dad had no clue how much the butcher was seething about this injustice, until one day he happened to come into Footscray Halal Meats alone and the guy behind the counter gave him such a serve. Obviously that wasn’t what was happening, he had the wrong end of the stick, but both my parents were kind of touched that the butcher was looking out for our family. My mum was maybe slightly more touched than my dad.

Jinghua: That’s very cute. I used to buy late-night emergency lube from this Club X. I remember asking if they had it in a pump bottle instead of a tube so I could get at it one-handed, and the guy behind the counter was like, “well a lot of good things in life take two hands, you need two hands to take off a bra,” and I was like “no you don’t, you need more practice”. It was a good time.

So why did your parents move to Footscray in the 80s, Liz?

Arts and gentrification

Liz: They were living in Richmond before, and they were renting but they couldn’t afford to buy a house. Then they saw that you could get a house in Footscray for like $20,000 or something, which was cheap even then.

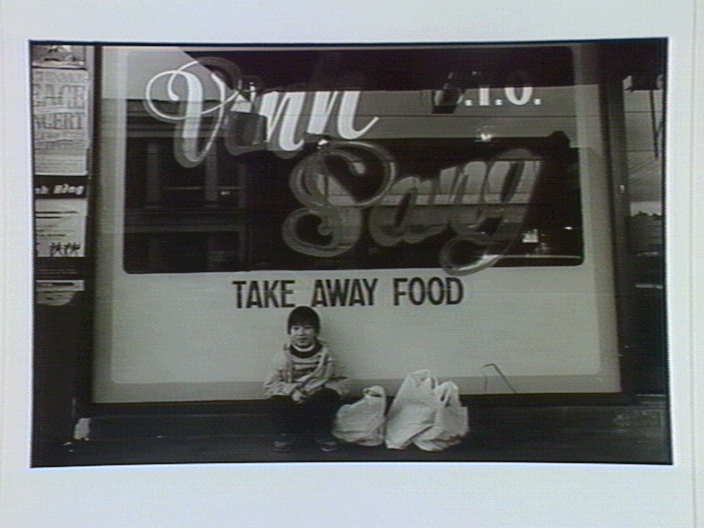

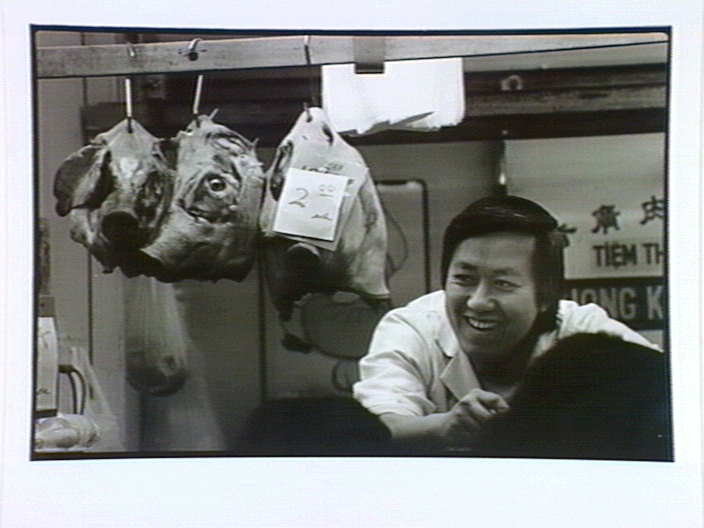

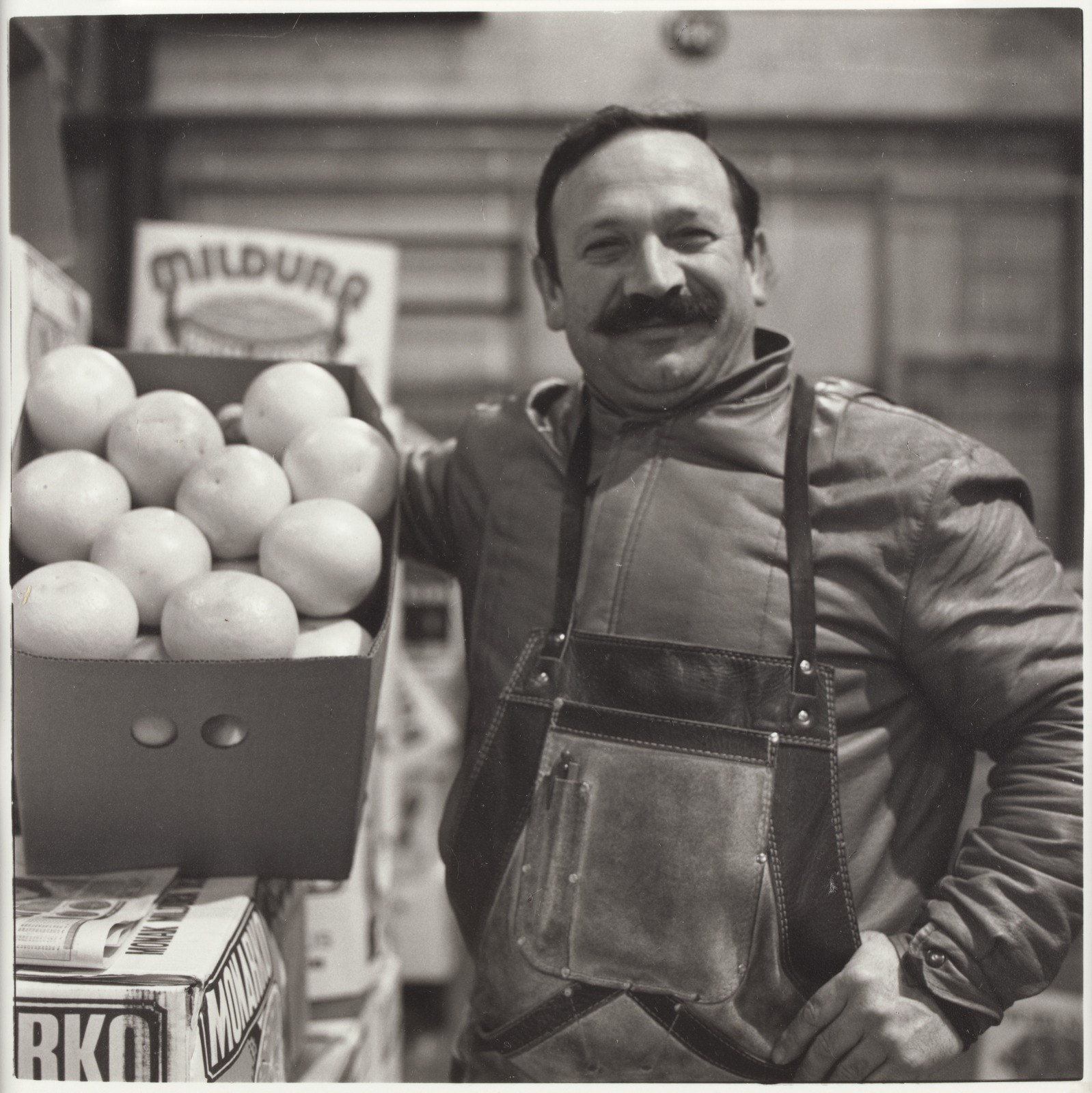

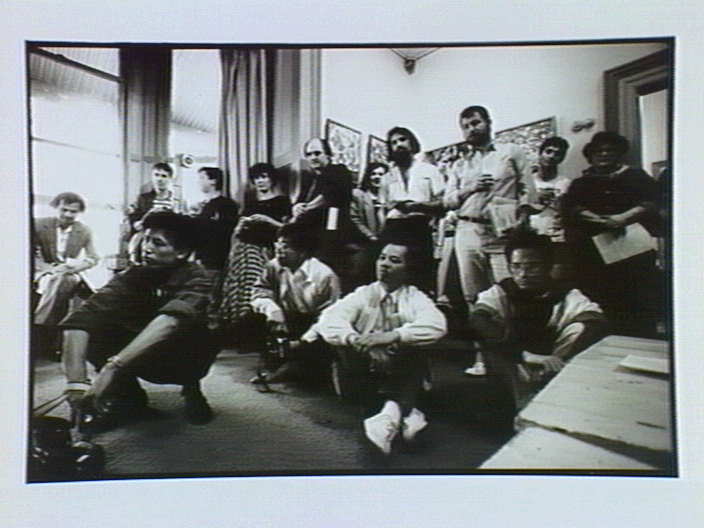

Footscray in the late 1980s (when Liz was born!) by photographers Elizabeth Gilliam, Dyranda Prevost, and Emmanuel Santos.

And the reason it was so cheap is really depressing — it’s that the Department of Housing was flogging off all its public housing stock at bargain basement prices. They deliberately wanted to make Footscray a more expensive place to live, and have people in private housing who had a vested interest in the dollar value of their property rising.

Jinghua: Wow, I guess that’s kind of the basis of all gentrification. And that’s well before what most people would think about as the gentrification of Footscray.

Liz: Yeah, people often mix up the cause and effect and timeline and order of events with gentrification. People I know who are always saying “there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism” still often have this attitude of “oh, don’t move to Footscray unless you’re authentically working-class or a migrant, because that’s causing gentrification”. That’s a consumption-based analysis, it’s ethical consumption, it’s navel-gazing, and I think it’s pretty pointless. The gentrification of Footscray is about decades of government policy that treat housing as primarily a way to increase wealth for developers and rich people. It’s annoying when hipsters from Kew decide that Footscray is cool now and feels safer for some reason, but that’s not the cause of gentrification, it’s just a symptom.

Jinghua: Yeah, I moved to Footscray in 2012 and to this flat on Nicholson St in 2013, and there were definitely a lot of those conversations and hand-wringing about new restaurants opening. But I wondered about contributing to gentrification as an artist — I did a few poetry readings at the Dancing Dog for West Word and Emerging Writers Festival, and in 2015 I did one out of my bedroom window for Big West Festival which was super cool, I loved doing that, but I was also like hmm is this attracting the same crowd as those food tours that seem to treat my block as a human zoo.

Liz: The arts do contribute to gentrification, but again, it’s at the policy level. Governments often give arts funding to artists in areas with low property values to attract visitors and investment from outside the community, then they cut that funding once artists have fulfilled their function and driven up the rents. That’s already happened to a lot of the artist collectives that used to be around in Footscray in the 90s.

Jinghua: Is there anything artists can do to resist that?

Liz: As individuals? Not really. You can try and be aware of the ways you’re being used, but it’s pretty relentless. You can only resist gentrification collectively. So I think an important first step for artists in gentrifying communities like Footscray is building relationships with already existing collective organisations in the local area — tenant groups, migrant organisations, Indigenous organisations. Just be part of the local community — the whole community, not just other artists.

The ANA clock

Jinghua: Okay so now if we keep going back up Nicholson Street, we kind of come full circle.

Liz: Yeah, so at the corner of Nicholson and Paisley, next to the Welcome Bowl sculpture, there’s a fairly shabby clock tower. I didn’t make the connection until recently that this clock was donated by the Footscray branch of the ANA in 1986 to celebrate their centenary. And more than that, the ANA are still around! They merged with another friendly society to become Australian Mutual.

The clock is always at the wrong time, but not at the wrong time in any predictable way — some days it’s 15 minutes ahead, other days it’s 45 minutes behind. I can never figure out what the pattern is. In the same way, history is rarely linear. Change is full of stops and starts, a few steps forward, a few steps back.

Jinghua: It’s also in front of my favourite shop in Footscray, which is a combination tobacconist, dry cleaner, key cutter, orchid florist. It’s a somewhat incongruous mixed business and that feels like a metaphor as well — something about how many things can be true at once.

The past isn’t a single coherent narrative, it’s full of fundamental ideological conflict, and often in surprising ways, like how union organisers, who I would typically think of as on “our side”, were some of the most virulent anti-Chinese campaigners. But it’s also inspiring to see that there has always been resistance. Nothing is a given, and there’s nothing natural or inevitable about white Australia — it’s a fantasy that’s never been realised.

Outro music is ‘What’ll we do when this is over?’, composed by Jack Davey and performed by Al Royal and Nicholas Robins at the Arcadia Theatre, Chatswood NSW, circa 16 December 1942.

Sources cited

Jinghua Qian, ‘Things and their makers: From “European labour only” to “ethical consumerism”’, Right Now, 8 September 2015.

Melbourne’s Living Museum of the West, Still Here: A brief history of Aboriginal people in Melbourne’s west, 1996. This exhibition, now largely digitised and available online, tells the story of how Aboriginal people have always lived and worked in Melbourne’s west.

Maribyrnong City Council, ‘Heritage Trails and Walks‘, accessed 20 June 2020. The map includes information on several Aboriginal activists who lived in the area, including Margaret Tucker, William Cooper, Lynch Cooper and Sally Russell.

‘Moneyocracy‘, The Independent, 23 September 1899.

‘The Yellow Agony‘, The Independent, 4 November 1887.

‘Woman’s Rights‘, The Independent, 23 November 1891.

Jinghua Qian with Megan Cope, Ihab, Naup Waup and Liz and Lloyd Patterson, ‘Inter Views‘, Big West Festival, Footscray, 2015. This was a live event (a streetside talk show) and a series of recordings about the western suburbs of Melbourne.

Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier, Gentrification and the Revanchist City, Routledge, 1996.

“For the real estate industry, art tamed the neighborhood, refracting back a mock pretense of exotic but benign danger. It depicted the East Village as rising from low life to high brow. Art donates a salable neighborhood “personality,” packaged the area as a real estate commodity and established demand. Indeed, ‘the story of the East Village’s newest bohemian efflorescence,’ it has been suggested, ‘can also be read as an episode in New York’s real estate history—that is, as the deployment of a force of gentrifying artists in lower Manhattan’s last slum’ (Robinson and McCormick 1984:135)…. By 1987, however, the marriage of convenience between art and real estate started to sour, and a wave of gallery closures was precipitated by massive rent increases demanded by landlords unconstrained by rent control.” (pp. 18-19)

“To explain gentrification according to the gentrifier’s preferences alone, while ignoring the role of builders, developers, landlords, mortgage lenders, government agencies, real estate agents—gentrifiers as producers—is excessively narrow. A broader theory of gentrification must take the role of the producers as well as the consumers into account, and when this is done it appears that the needs of production—in particular the need to earn profit—are a more decisive initiative behind gentrification than consumer preference. ” (pp. 54-55)

Rimi Khan, ‘Case Study: Creating a Profile – Reworking “Community” at Footscray Community Arts Centre’ Local-Global: Identity, Security, Community, v.7, 2010, p.134-148 (ISSN: 1832-6919)

For further reading on gentrification, Liz recommends The gentrification reader (Routledge, 2010), edited by Loretta Lees, Tom Slater and Elvin Wyly.