Vice Hole

Under cover of darkness, queers, Christians, drinkers, firefighters, Communists, MPs, and Chinese laundry workers spar over who’s a worker, and who’s a threat. The battleground for solidarity is right here, underfoot.

Content note: This piece is about the way bigots represent marginalised people as sexual threats. It contains references to sexual assault and sexual coercion, including child sexual abuse and labour trafficking.

Map

Use the icon at the top left to toggle which tracks are shown, and “star” the map to save it to your Google Maps.

Transcript

A Pestilent Vice Hole (Mechanics Way)

Liz: Okay, so “The Napier St Toilet is a pestilent vice hole stuck in the middle of Footscray,” said Councilor Bill Kelly in a 1959 Footscray Council meeting. He said it was an “educational centre for perverts of the future”. He said he wanted it blown up.

The toilets were shut down, but they weren’t blown up. They’re right here, on a nature strip in what’s now called Mechanics Way.

Jinghua: There’s nothing here though.

Liz: Well, that’s because they’re underground toilets. The council shut the toilet’s doors and filled them in and planted grass over the top, and most people forgot they were here, but they are still here, pretty much intact, underfoot.

When they were built in 1936, toilets were often put underground for decency — the idea was that nobody should have to actually see the toilets. But there was this tension: privacy around bodily functions is decent, is respectable, but when there’s too much privacy, that creates perverts — and a vice hole!

Jinghua: So when they say perverts, do they mean queers?

Liz: I think so, but it’s hard to tell!

Jinghua: I guess in historical sources, it’s often really hard to tell what people mean by “indecency” or “obscenity” or “perversion”. I mean, it could mean something to do with queerness, or it could be pissing in the street, or it could be sexual assault. It’s this undifferentiated blob of sexual transgression.

Liz: It’s sad as a queer person, going through the archives. You know that queer people have always existed, but it’s hard to find unambiguous evidence of that in archives, and when we do, it’s often tied to this idea that we’re inherently a sexual threat. It’s depressing, honestly.

Jinghua: That’s so often the case, isn’t it? I feel that looking at the white Australia policy photo archives too, and even reading court records: often we can only find ourselves in the archives because of criminality and policing. The only documentation you have is from these hostile encounters with the state. It’s bittersweet.

Hen Assemblies (Federal Hall, Nicholson Street)

Liz: Which brings us to another ambiguously queer incident in local history. Looking straight across the street from here, you can see a modern-ish building housing the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre. But in 1908 that site was a venue for hire called Federal Hall where a number of single-sex balls were held.

The first few were for women. They were costume balls with half the guests dressed as men, and they would romance the guests dressed as women. And that got mocked by Punch, a culture magazine, but when Footscray men decided to have a men-only ball, Punch was like “ok, this is not a joke anymore”. They started using language like, “we can have only sniggering contempt for the men who would participate in such a thing”.

The Footscray media didn’t take the Punch meltdown that seriously. They reprinted the whole homophobic Punch article with this introduction that was basically, “get a load of these guys, taking everything so seriously”.

Jinghua: I really enjoyed that, the “OK Boomer” energy of the Footscray paper’s response. So these balls were queer, right?

Liz: I mean, you’d have to assume for some participants, yeah, they were. But it was all in the realm of plausible deniability.

Right up until the postwar period, drag in Australia was completely mainstream entertainment. It was seen by most people as just costume, nothing to do with sexuality or gender identity. You have to remember as well that drag performers were often part of variety shows that included minstrel performers and yellowface acts and Jewish impersonators, that kind of thing — that’s something that’s really important to highlight, that racist, mocking element, historically, to this kind of theatre and play.

Jinghua: Yeah wow, I guess you still sometimes see that in drag.

Liz: Yeah, and the same-sex balls were like that too: people weren’t just in drag, they were playing a role, having a laugh. So if you were using this role-play of a costume party to try out a different gender or sexual role, you could kind of hide in plain sight.

Jinghua: There’s a lot of hiding in plain sight in all these stories.

If we go up Nicholson St a bit, there’s a park you can enter on your right, just before the railway bridge. That’s Railway Reserve.

A Communist Amazon (Railway Reserve)

Liz: In 1942, Moira James, the first ever female organiser for the Munition Workers Union organised a rally in Railway Reserve of munition factory workers, who were predominantly young women.

Moira was also a Communist. The local MP, a Labor Party man called Jack Mullens, described her as a:

“Communist amazon… strong in physique, but doubtful in her femininity.”

And talking about her work organising young women factory workers, Mullens said:

“…a decent, refined, unsophisticated girl […] suddenly finds herself in an environment due to the war, working in an industry where she can be bossed, body and soul, by a domineering creature such as Moira James.”

Jinghua: God, he really attacks her as this predatory butch character.

Liz: It’s pretty wild. I would love it if she was a lesbian, but we have no actual evidence either way. It’s basically just an attempt to use homophobia to discredit her.

Jinghua: It’s interesting how he projects worker exploitation onto the union organiser, too: “bossed body and soul”. Like, we all know this kind of attack, the way it paints her as not a real woman but instead a threat to women. Obviously that happens a lot to trans women, butch women, Black women, intersex women even now — you see it in the transphobic debates around toilets, you see it in women’s sport. It’s this idea that you have to exclude all these women to protect real women.

There’s a very specific type of woman who’s worthy of protection, and usually it’s not a real woman. It’s a mythical figure of frailty that’s weaponised against people of colour, against trans and intersex people, against women who aren’t sufficiently feminine. The “real woman” is a hypothetical woman.

Liz: Which is an idea that’s often promoted by women themselves, particularly white women — that women, white women, are the pure, respectable, moral guardians of the community as a whole. Which brings us to the temperance movement.

Tremble, King Alcohol (Temperance Hall site)

Liz: So if we go through Railway Reserve and over the railway tracks onto Leeds St, near the corner of Leeds and Paisley, you can see a building that’s currently a mobile phone store. That building was once Temperance Hall, the headquarters of the anti-alcohol movement in Footscray in the late 19th century. This was a really popular movement, especially with women.

Jinghua: That’s kind of surprising given so many of the early buildings in Footscray were pubs.

Liz: Yeah, the temperance movement was not popular with everyone. During the peak of the temperance movement, for example, there were two firefighting brigades in Footscray. One was sponsored by a local pub, and one was exclusively for non-drinkers. One time they both arrived at the same fire on Barkly St, but there was only one fire hydrant in the street. They had a full-on street brawl over who would get to use the hydrant. One guy cracked his skull and nearly died. That’s how much drinkers and non-drinkers hated each other’s guts.

Jinghua: A lot of the people that temperance advocates came into conflict with were socialists. Footscray was obviously a working-class community and it was a heavy-drinking one. And many temperance advocates looked at that situation and said: what we need to address here is the drinking. If people would just keep themselves nice, maybe they wouldn’t be having the problems with disease and poverty and exploitation that they were having. And socialists, of course, thought that was paternalistic and that the real problem was capitalism.

Liz: And I definitely agree with that — but the reality is that the drinking culture around here was actually really intense and it would’ve been good if, as a community, we’d reflected on that. Instead what happened is that white socialist men leaned into this masculine, hard-drinking persona, in opposition to the female-dominated temperance leagues. So, that kind of Jimmy Barnes, blunnie, flanny, moustache, Working Class Man, footy shorts etc vibe.

Jinghua: Well that definitely feels familiar — this way of defining the working class through these subcultural affectations instead of, I suppose, material experience. It doesn’t leave a lot of room for anyone else. It’s so often a way of making women, migrants and people of colour invisible in the working class and in the labour movement. And it makes entire industries invisible as well — keeping the figure of the worker to a shrinking set of old-school “blue collar” jobs while exploitation in cleaning, hospitality, care work, call centres, and pretty much everywhere else doesn’t get the same romanticised attention.

Liz: Yeah, that kind of association of workingclassness with this hyper-masculinity is, I think, one of the reasons why homophobia was such an effective line of attack against people like Moira James. And in the same way, white labour activists worked hard to associate working-class identity with whiteness.

One Chinese Man A Factory (Ming Sing’s Laundry, corner Leeds and Hopkins street)

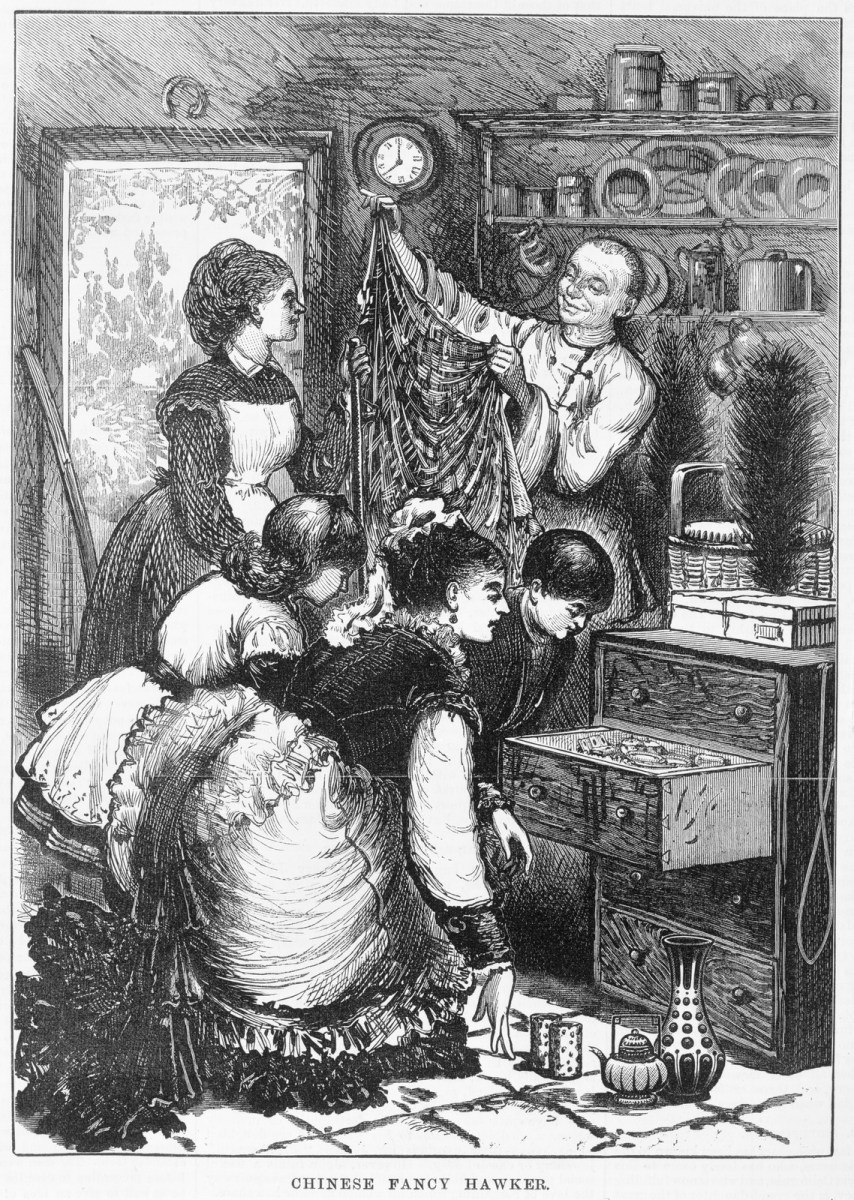

Jinghua: If we keep going up Leeds and hit Barkly/Hopkins, there were a lot of Chinese businesses here that were prosecuted under the Shops and Factories Act in the late 19th/early 20th century. The Act came through in 1896 after a lot of lobbying from white labour activists who basically argued that all Chinese businesses were sweatshops until that got enshrined in law.

The Act defined a single Chinese person as a factory. Even white people recognised it was pretty unfair, like obviously that’s not really about worker exploitation. In 1902, Ming Sing, a Chinese guy who had a laundry on Hopkins St near the corner of Leeds, was charged because he was ironing late on a Friday night and the Act said he couldn’t work past 5pm. He tried to say that he didn’t work on Mondays and Tuesdays but Fridays were always busy because he had to get everything done for the weekend. It’s basically the worst of both worlds, right, being a sole trader but not being able to work your own hours. Anyway the judge was sympathetic but Ming Sing still had to pay the fine and costs.

Liz: Another part of the anti-Chinese movement was the idea that Chinese men were a sexual threat to white women, and specifically that they might lure white women into sex work. But also, there was a lot of kind of weird lurid language flying around that implied Chinese men were kind of gay?

Jinghua: Yeah it’s that undifferentiated sexual transgression again, right, like in the 1800s the anti-Chinese rhetoric really draws from every well. So because most of the Chinese migrants were men, you see this stuff like “ooh, what do all these Chinamen get up to together” alongside panic about protecting white women. So whether or not the sex is paid, whether or not it’s consensual, it doesn’t really matter because it’s all still miscegenation.

There’s this article from the Footscray paper in 1887 titled “The Yellow Agony” and it says that Chinese men’s want of moral training is “such that they have no objection to clubbing together and maintaining one frail female in semi-luxury but sickening debauchery”.

Liz: They manage to make it sound pretty good to be honest! But, you still see most of the same arguments today, just with some bits rearranged.

Jinghua: Yeah I do think it’s interesting how it’s been rearranged — like these days, Chinese and East Asian men are often desexualised. White nationalists have transferred that sexual threat onto Black men and Muslim men. And Asian women are represented as kind of inherently tied to the sex trade, whether as trafficking victims or just garden-variety gold diggers. That’s faded a little now as well compared to when I was growing up but it’s definitely still lingering.

And then on the Shops and Factories Act, too, Australian trade unions still use faux concern for migrant workers to frame them as a threat to Australian workers, to real workers.

Liz: Which is also interesting, actually, because that is exactly the attitude Moira James, the Munition Workers Union organiser, came up against when she was arguing unions should support equal pay for men and women. Fundamentally, Trades Hall Council, the peak union body in Victoria, saw their role as protecting men’s jobs, and working women were a threat to that. Trades Hall only supported equal pay when it became obvious that it wasn’t possible to keep women out of men’s jobs entirely anymore. But they framed it as about protecting women, too, from rough or dirty jobs.

Jinghua: What a lot of these tensions seem to be about is who has the right to be thought of as a worker rather than a threat to workers. And that threat is often described as a sexual threat.

Liz: Footscray for most of its history was an industrial centre. People took a lot of pride in that, it was a big part of the community identity. It still is, to an extent. So this is a place where tensions over who belongs here, who is respectable often take the form of: who is part of the working class?

Jinghua: That’s definitely still a tension. At the moment I’m a freelance writer which is a strange situation because even though there’s a giant glaring power imbalance between me and most of the media companies I write for, I’m supposed to negotiate as if I’m a business and they’re my clients. Effectively, as if I am a factory! It’s really hard to organise as freelancers for a billion reasons but I think one barrier is the idea that writers aren’t working class, as if we get paid in cultural capital. Which of course just means that only rich people get to be writers.

Liz: I’ve had some similar experiences. Often people will say, Liz, you’re really middle-class because I’m an ex-academic who’s read a bit of Deleuze, but once they learn that my dad is a plumber and I grew up in the Western Suburbs and I know how to hold a hammer, they think they’re mistaken and see me as really working class.

I don’t think either of those things are what class is about. I think class is mostly about money and how you get it. Most people rely on work or welfare to survive. That’s what was originally meant by the working class, right? People who have nothing to sell but their labour, people who have to work. And we have more in common with each other than the people we might be working for.

Jinghua: It’s beyond disappointing, it’s actually just tragic the way that this narrow thinking around the working class can foreclose possibilities for solidarity. Across gender and race and different industries and ways of working and, of course, across borders. Work is more and more casual and more and more global so we’re doomed if we can’t figure out how to reach across.

Liz: Which is basically why we did this project on Footscray’s history.

Jinghua: Because we’re big COMMUNISTS!

Liz: We are! We’re big communists and we believe in solidarity, and there’s so much potential for solidarity across difference in places like Footscray. But to get there, we have to acknowledge the ways we’ve fucked each other over so we can move beyond divide-and-conquer politics and focus on the real enemy, focus on our shared enemy.

Jinghua: Who is our shared enemy, Liz?

Liz: People from Yarraville!

Outro music is ‘What’ll we do when this is over?’, composed by Jack Davey and performed by Al Royal and Nicholas Robins at the Arcadia Theatre, Chatswood NSW, circa 16 December 1942.

Sources cited

Victorian Heritage Database report on the Napier Street/Mechanics Way underground toilets.

“A Pestilent Vice Hole.” Footscray Advertiser, Feb 5, 1959, p. 16.

The real face of White Australia. Invisible Australians. Accessed 26/07/2020.

Eleven women in a mock “Wedding” photograph. C. 1930. Footscray Historical Society, via Picture Victoria.

“Church and Organ.” Punch, 9 July 1908.

“Hen Assemblies.” Punch, 9 July 1908.

“Dance for Men Only. A Unique Function.” Independent (Footscray), 15 August 1908.

“UNMIXED DANCING. Punch’s Solemn Voice.” Independent (Footscray), 18 July 1908.

“News in Brief.” Independent (Footscray), 10 May 1890.

“Women war-workers help run trade unions.” Australian Women’s Weekly, 08 Aug 1942.

“Victorian News.” The Australian Worker (Sydney), 15 Apr 1942.

“Women In War! Hear Communist Women Speak.” The Herald (Melbourne), 13 Nov 1942.

“A Victorian Communists’ Who’s Who. An Extract from Hansard.” Advocate (Melbourne), 02 Aug 1944.

Women’s Christian Temperance Union of Victoria pledge certificate, 1907.

Sally Wilde. “Life Under The Bells: A history of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade, Melbourne 1891-1991”, 1991.

Fiery Firemen. Standard (Port Melbourne), 1 Jan 1887.

Factories Act of 1896. “‘Factory or work-room’ shall mean— any office building or place in which four or more persons other than a Chinese or in which any one or more Chinese persons are or is employed directly or indirectly in working in any handicraft or in preparing or manufacturing articles for trade or sale.”

“One Chinaman a Factory. A Sympathetic Bench.” Independent (Footscray), 29 Mar 1902.

“The Yellow Agony.” Independent (Footscray), 04 Nov 1887.

“Mr A.W. Coles, MHR, Under Fire. THC’s Objection To Replacing Men With Women In Industry.” Labor Call (Melbourne), 01 May 1941. This 1941 Trades Hall Council debate over the issue of the approach trade unions should take to equal pay for women presents a fascinating microcosm of the range of views within the Australian labour movement on the issue.

Further reading

Fancy dress balls for women appear as intermittent fads in Australian newspaper events reporting from the late 19th century until the late 1930s. See search results for “ball for women only” in the Trove archives; also results for “ball for ladies only”. The earliest reference we could find in Australian media to an event like this was to an 1888 ball in Boston. The Advocate (13 Jun 1908) claims Footscray introduced the fad to Australia; in fact, the earliest Australian ball for women only appears to have taken place in Adelaide in 1889. Footscray merely revived it for the 20th century.

Balls for men only do not appear to have taken off in the same way; however, male drag performers (known as female impersonators) were mainstream popular entertainment through the post-war period. The Trove digital archive contains a number of photographs of female impersonators in Australia from as early as 1870.

Temperance Hall was renovated to serve as a Masonic Lodge in the late 19th century. More about the building and its history can be found in the Footscray Central Activities Area Heritage Citations Report 2014.

We originally read the story about the duelling firefighting brigades in “Charlie Lovett’s Footscray: being the reminiscences of Charles Eldred Lovett”, a collection of columns first published in the Footscray Mail 1935-36 and edited by John Lack, published by the Footscray Historical Society in 1993.

The Firemen’s Fracas at Footscray. Bendigo Advertiser, 14 Jan 1887 (via The Herald (Melbourne), 13 Jan.) Court proceedings relating to the brawl.

Some conflicts between socialists and temperance advocates through the decades:

Toscin (Melbourne), 21 Dec 1899.

The Independent (Footscray), 29 Feb 1908.

YARRA BANK. PROHIBITION AND PROFITEERS. The Socialist (Melbourne), 20 Aug 1920.

“The Farce of No-Licence” The Age, 26 Mar 1930.

Ming Sing registers as a sole trader, 1899.

Ming Sing would be assaulted in the street later in 1902. Nightmare year. Prosecution of another Chinese laundry sole trader on Hopkins Street under the Factories Act, Wing Yick. Independent (Footscray), 28 Mar 1903.

More on Chinese Australian workers’ history:

Jinghua Qian. “Things and their makers: from ‘European labour only’ to ‘ethical consumerism.’” Right Now, 2015.

Liam Ward. “Radical Chinese labour in Australian history.” Marxist Left Review, Winter 2015.