You can listen to my essay on the politics of changing my name here via Soundcloud. Kim Cheng Boey’s poem for Silent Dialogue is also available as audio, or you can order a print copy of the Silent Dialogue book here featuring Maria Tumarkin, Elizabeth Tan, Julie Koh and many more.

Eating with My Mouth Open | The Saturday Paper

I grew up thinking there were seven fundamental flavours: suān, tián, kǔ, là, xián, xiān, má. The first five translate easily – sour, sweet, bitter, hot, salty – but the other two don’t own a home on the English tongue. It was a shock to realise that something as material as flavour could be coloured and even erased by language. But eating has many dimensions beyond what happens in your mouth, as Sam van Zweden chronicles in this thoughtful debut, Eating with My Mouth Open.

– Eating with My Mouth Open | The Saturday Paper

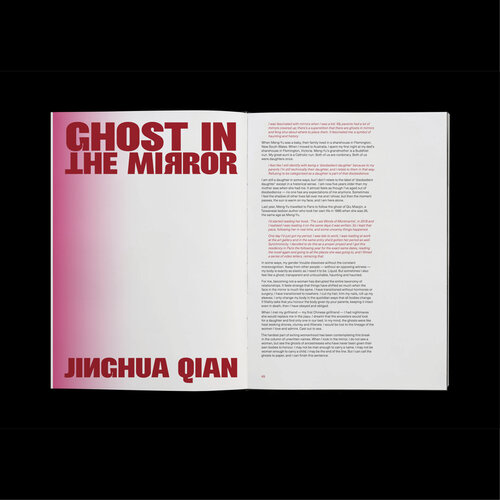

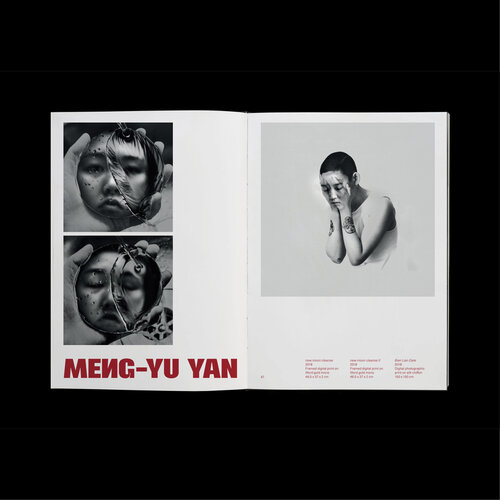

Ghost in the mirror | Disobedient Daughters

I have an essay in this gorgeous publication that accompanies the Disobedient Daughters exhibition at Counihan Gallery. Edited by curator Sophia Cai and designed by Joy Li, you can order a copy through the publisher, Heart of Hearts Press.

If you’re in Melbourne, please also check out the exhibition which is on at Counihan Gallery, from 6 February to 21 March. Thank you especially to artist Meng-Yu Yan, whose work my piece riffs off.

Saving Face | The Guardian

For the Guardian’s Stream Team column, I wrote about the 2004 romcom, Saving Face. Smash Valentine’s Day and the Year of the Ox with this gaysian classic that celebrates mothers and daughters pushing back on patriarchy, shame and prejudice.

Event: Silent Dialogue book launch

There’s a book launch for Silent Dialogue 沉默的对话 tomorrow night in Collingwood if you’d like to join us in a celebration and meet some of the folks involved in the project. The book is an illustrated multilingual publication that accompanies the Silent Dialogue exhibition with images of original artworks and specially commissioned pieces of original writing by leading scholars and writers from across the country. I’ll be reading from my essay in the book, ‘We need new names’, which looks at the politics of changing your name.

Fri 5 Feb 2021

6:15 pm to 7:30 pm

Art Echo Gallery, Collingwood

free | booking required

You can also order the Silent Dialogue book here.

Not For Broadcast | The Saturday Paper

‘[Evading censorship] felt a lot like a game, actually – a futile yet addictive game that made your heart race as you tried to jump from story to story, ducking and weaving, squeezing as much as you could through an ever-shrinking space.’

For The Saturday Paper’s culture section, I wrote about reliving the anxiety and adrenaline of working as a journalist in China while playing the dystopian newsroom simulation game Not for Broadcast. Read it here.

I can’t apply for another grant | un Magazine

‘Arts funding is a cancer. Applying for it has become its own job, a job no one enjoys or wants.’

For un Magazine 14.2, ANTI/ANTE, I wrote about the perverse relationship between art, money, and survival, and why I want to set it on fire and start over. Read or listen at the link.

I can’t apply for another grant

Jinghua Qian, ‘I can’t apply for another grant’, Un magazine 14.2 (print, audio and digital), November 2020. Edited by Elena Gomez.

My friends keep sending me grants and opportunities. I appreciate it, I really do. It’s nice to know that people are thinking of me. But I never want to apply for a grant again. I can’t. My body recoils. It feels like taking my skin off for nothing.

We’ve all been talking a lot this year about the perverse relationship between art, money and survival. ‘Artists are in a constant state of precarity and crisis,’ I wrote in July. ‘For many of us, there’s nothing to return to, nothing to recover. The status quo is already broken. It’s an empty bowl — with a smear of racism, sexism and ableism to boot.’

In August, I followed up with an opinion piece in The Guardian about going on the dole and navigating the sadistic and absurd mutual obligations system for welfare recipients: ‘It does nothing to help people find work. It’s just a complicated, expensive way of penalising people for being poor.’ But as awful as Centrelink is, arts funding is somehow even worse. At least the dole is ongoing and not a lottery. Arts funding bodies, on the other hand, want you to craft a 10-page proposal to compete for a minuscule chance at a trickle of money. One template rejection I received this year said that only six per cent of applicants had been successful. Another rejection came to me five months after applications had closed. In both cases, the grants themselves were less than $5,000 — not even three weeks’ worth of the average weekly earnings for a full-time adult worker in Australia.1

The quick-response grants that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic were often no better. My eyes glazed over as I scanned the same buzzwords: resilience, adaptability, relief. Each time I was left confused about whether these grants were intended to provide for my welfare or to fund new projects and activities — whether they were offered as charity or investment. Each time I felt like I was handing in my CV and portfolio at the soup kitchen counter. Each time my shoulders seized, awaiting judgement, anticipating rejection. This is not relief.

For all its faults, JobSeeker is easily the most effective arts funding program in this country. Going on the dole has helped my career and my craft far more than any arts grant ever has. Knowing that the fortnightly payments will at least cover my rent is a huge relief, pulling the plug from my brimming tub of baseline anxiety. It’s also given me more intellectual and creative freedom because I’m less reliant on fitting my vision to the categories and priorities of funding bodies. I don’t have to contort my work so that it speaks to diversity instead of antiracism, inclusion instead of decolonisation, identity instead of ideology, or other bureaucratic definitions that are always just slightly misaligned with my own thinking.

Thanks to JobSeeker, I’ve done some of my best work this year. In fact, I’ve been weirdly prolific, pitching and publishing more than ever. I’m much more comfortable pitching to editors than applying for grants. Media and publishing is still subject to commercial imperatives, of course, and that comes with its own set of problems and limitations, but the grant process feels particularly alienating, disheartening and disruptive. All I ever want from the arts funding bureaucracy is time to write, and JobSeeker gives me that without getting between me and my audience. I think if more people could access the dole, and the rate were higher, it would make an enormous difference to cultural life. I would rather arts organisations fight for that than for more arts funding.

Most independent artists are already working across a range of industries in order to survive, and many rely on welfare, but often arts advocacy tends to emphasise how art is exceptional. I think it’s worth taking note of the peculiarities of making art, but we can’t lose sight of the bigger picture. We need to organise in solidarity with workers in education, media, publishing and other cultural industries, and even beyond. I’m not convinced that it’s useful or even truthful to focus narrowly on how artists are special when our needs are the same as those of all precarious workers — of all people.

The pandemic has generated plenty of chatter about saving the arts, but it’s also burnished the deep ambivalence many of us feel about this sector and how it operates. In the conversations I’ve had with other artists, there’s always an undercurrent of revolutionary rage. We’ve all been talking about how this year offers an opportunity to rethink this sector — what if we set it on fire and started over?

Arts funding is a cancer. Applying for it has become its own job, a job no one enjoys or wants. I’m not sure that anyone is even funding the arts, really — it feels more like art happens by accident as a decorative footnote to the work of endless applications, assessments, acquittals and evaluations. I’m sure some of these elements were once designed as accountability mechanisms, but they have grown monstrously out of control. Like the mutual obligation system for welfare recipients, the arts funding process is disproportionate and counterproductive. There are easier ways to give artists money.

I think a competition-based funding model is inherently destructive. I don’t understand why it’s accepted that in the arts, sport and entertainment industries a tiny elite should profit and everyone else should suffer in poverty for daring to try. Even under capitalism, that’s not how it works in most professions. Funding shouldn’t be a prize or an honour, it should provide a living wage so people can make art without some other source of wealth or income.

We’ve all been talking about this for such a long time and I’m so tired of it. I don’t want to tinker with this system, shifting the priorities and massaging the language. I’m not excited about heralding a new cohort of gatekeepers. I’m not interested in diversity and inclusion. I just want to overthrow capitalism already.

Ultimately, I don’t believe in meritocracy. I don’t believe in excellence. Survival is not a reward. We all deserve to have our basic needs met.

I don’t understand why it’s easier to get paid to administer arts funding than to make art. I don’t understand most of the jobs that exist in this society — they seem to bear no relation to the world that I live in or what it needs. They bear no relation to what I understand as value or a life worth living. Capitalism devalues so much work that’s important and necessary while creating jobs that just tick boxes and move money around. I think that might be the most dystopian thing in this hellscape. We live in a time when no one needs to be hungry, homeless or overworked. It should be possible for all of us to thrive. I want a radical redistribution of time and resources, a reimagining of labour and value. I want to unravel this tangle of art, money and survival so that the next time we talk about this, it’s an entirely different conversation.

1. For May 2020, full-time adult average weekly earnings in Australia were $1,713.90. See: ‘Average Weekly Earnings, Australia,’ Australian Bureau of Statistics, 15 August 2020.

Jinghua Qian is a Shanghainese writer living in Melbourne, on the land of the Kulin Nations. Ey has written on desire, resistance and diaspora for Overland, Meanjin, Sydney Morning Herald and The Guardian.

Ellie & Abbie (& Ellie’s Dead Aunt) film review | The Guardian

For The Guardian, I reviewed Monica Zanetti’s teen romcom, Ellie & Abbie (& Ellie’s Dead Aunt), a pretty charming story of queer love – romantic, familial, and intergenerational.

‘Zanetti cleverly plays with the idea that our queer predecessors paved the way for how we live now, but as individuals can be just as bumbling and out of touch as anyone else when it comes to dealing with teenagers. We might idolise OWLs (“older wiser lesbians”) but they’re only flightless, bug-eyed humans after all.’

Walking away, backwards | Feminist Writers Festival

Edit: Sadly Feminist Writers Festival has shut down. Here’s an archive of my article.

As an AFAB nonbinary person, many feminist and women’s spaces welcome me – but often that welcome is itself a form of trans erasure, an insistence on seeing us as the genders we were assigned. I wrote about my uncomfortable relationship with feminist literary spaces for Feminist Writers Festival.

‘I’m pretty accustomed to not feeling at home anywhere – this is often a good thing, a productive tension. The can of worms fertilises the soil. But whether it’s Feminist Writers Festival, Facebook writers’ groups, or other feminist literary initiatives like the Stella Prize, I think it’s important to remember that you can’t simply tweak the category of woman to accommodate nonbinary people. Nonbinary disturbs the foundations of binary gender because it’s supposed to. It’s intentionally an interruption, a question as well as an identity.’